By Michael Apotria and Brokk Tollefson, SCSU Journalism students

Michael Apotria and Brokk Tollefson, journalism students at Southern Connecticut State University, reported this story in 2017 as part of Journalism Capstone coursework on World War I.

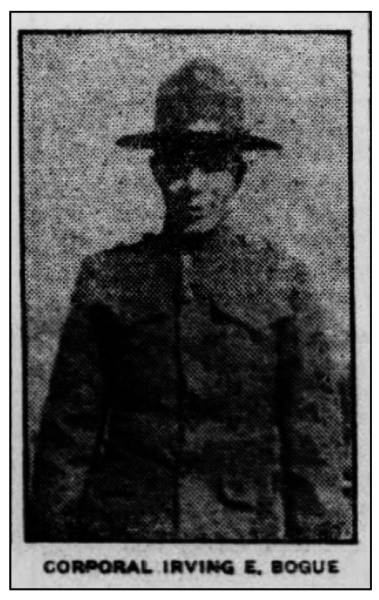

After a German gas attack in February 1918, Norwich native Irving Bogue brought his Army friend, Pvt. Walter Patrick Moran, to get medical attention.

“The next day, Irving Bogue goes back to check on his friend (Moran) at the first-aid station and they said, ‘I’m sorry, he didn’t make it. He’s over there.’ And they pointed to where the body bags were,” said Mary Beth Applegate of Wallingford, Moran’s grandniece.

Seeking one last look at his friend, Bogue opened the body bag: Moran was still breathing.

The story of how he was saved has become a family legend.

Moran was born on June 20, 1891 and worked in electrical repair before registering for the draft at age 26 on June 7, 1917.

“Walter was the first man from Norwich who had his name in the draft in Washington, D.C.,” said Applegate. “He was the first name drawn, the first one to get accepted after having his physical, the first one overseas and the first one wounded overseas.”

The details of the fateful battle in France appear in an article published by the Norwich Bulletin on March 27, 1918 and the book “Connecticut Fights; the Story of the 102nd Regiment,” by Capt. Daniel Strickland.

Moran, along with four other soldiers from the 102nd Regiment, was severely wounded by a German gas shell on Feb. 16, 1918. It landed two feet away from them. Moran suffered burns from his waist to his toes and had two pieces of shrapnel lodged into his leg, causing severe blood loss. He was then carried by three men from Norwich, including Bogue, to the closest first-aid station.

It wouldn’t be the last time that Moran beat death.

After Bogue saved Moran from the body bag, Moran would spend the next several months recovering from his injuries in a hospital just outside of Savenay, France called Base 8 — but no one back home knew he had survived.

For several weeks following the initial update of Moran’s stay at Base 8, he was unable to be located or receive mail. This led to many back in Connecticut to fear the worst.

It was another local friend who finally sent word home that Moran was OK.

Harry Kromer, also from Norwich, recognized Moran sitting upright in a hospital bed and passed on news that everyone was worried.

Moran wrote another letter home, which was published by the Norwich Bulletin, explaining he was not dead, but had just not been receiving the mail that was sent to him.

“Walter says he feels confident that he will get his mail, which will be a real genuine treat after being dead to all who where near and dear to him for over eight months,” according to the Norwich Bulletin.

While he recovered and survived the war, the man who can be credited with saving Moran’s life did not.

About a year later, on Feb. 25, 1919, the Norwich Bulletin published parts of a letter written by Sgt. William Bergin to Ruth Bogue regarding the death of her brother, Irving. The article stated that he was killed in battle 16 days before the end of the war on Oct. 26, 1918 by a machine gunner.

Following the war, Moran entered the workforce once again and continued working in electrical for a short time. He later became the head postmaster for Norwich.

Moran died at 81 in 1971 while in the Connecticut State Veterans Affairs Hospital in Rocky Hill. He is buried in St. Mary’s cemetery in Norwich with several other members of his family behind the Moran monument.

As a child, Applegate accompanied her grandfather on visits with Moran, but didn’t learn the depth of his service until after grandfather and Moran had both died. That’s when she found a scrapbook detailing his time during the war, which prompted her to ask her father stories.

Applegate said she wished she had found the scrapbook earlier.

“I wish I knew him better,” said Applegate. “I know now looking back and I do regret that. He was very giving and selfless.”