By Jeniece Roman and Matthew Johnson, SCSU Journalism students

Jeniece Roman and Matthew Johnson, journalism students at Southern Connecticut State University, reported this story in 2017 as part of Journalism Capstone coursework on World War I.

After one of the longest and bloodiest battles of World War I, Pvt. Vincent W. Atwood returned home from the war a different man.

Before leaving, Atwood was a “simple farmer” working on his family farm, according to his great-nephew Alan Crane, who himself is a World War I re-enactor. When he returned home, his family described him as being “a little off.”

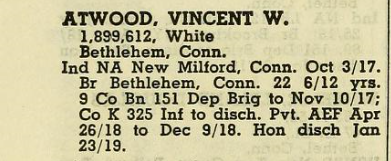

According to his enlistment records, Atwood was drafted when he was 22 years old. He joined the 82nd Division, known as the “All-American” Division, 325th Regiment, Company K.

Atwood told the family the first thing that they made him do when he arrived in France, was pick up the bodies of American soldiers from the battlefield and bury them. Atwood was sent to France in April 1918, but did not see the battlefield until October of that year.

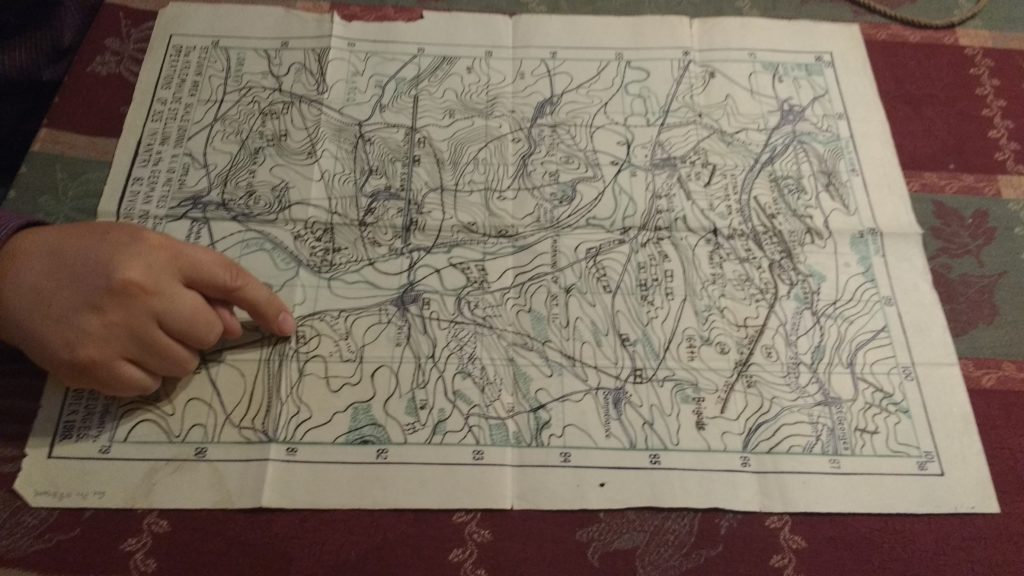

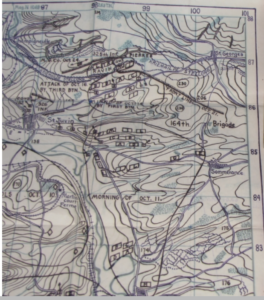

Company K was sent to fight in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, a battle that took place from Sept. 26, 1918, until the end of the war Nov. 11, 1918. Crane said that Atwood was in battle from Oct. 7 to Oct. 15, during the second phase of the long battle.

The Argonne advance was by far the hardest job that had been assigned to the American soldier, according to the article “Argonne Battle in Second Phase, Hardest Job Yet,” published in Stars and Strips on Oct. 11, 1918. “With fighting, savage bitter fighting in progress every hour of the day and night along the whole 20 miles that stretch westward from Meuse,” the article reads.

Crane said Atwood and his company launched an attack against the German position that was called the Kriemhilde Stellung, a defensive line named after Wagnerian Witches. The Kriemhilde was reinforced by long-standing trenches and was one of the most difficult lines to overtake. Crane said Company K made the furthest advance of that regiment against the line, broke through it and went into a ravine that the Germans had fortified.

“If you read the accounts of that fighting, it’s unlike anything that anyone’s experienced who’s alive today. They were shelled; they were gassed, hand-to-hand fighting with Germans, machine gunfire constantly,” said Crane.

They held the line for about 24 hours, but were then pushed out. Crane said that out of more than 200 men in Atwood’s company, only 40 men survived and Atwood was one of them.

“They got completely decimated during that fighting,” said Crane. “Somehow, he made it out of there alive when so many of the men he served with didn’t.”

Crane said that after the war was over, Atwood returned before the rest of his regiment and his family said that when he came back he was “a little off.”

“I never got any explanations of what a little off meant from anyone,” said Crane. “But they all said that he was not right after that.”

Crane said his family suspected that Atwood might have had shell-shock due to his experience in battle. After he returned to the United States from the war, Atwood disappeared. An estimated 10 years had passed before Atwood returned home to his family, but never mention where he went or why he left.

“He just left, he didn’t tell anyone where he was going or what he was doing,” said Crane. “You know, he was probably working out whatever demons that he had and that was how he dealt with it.”

When Atwood finally returned, he worked as a chef in various kitchens. Atwood died in a Veterans Affairs hospital in Rocky Hill, Conn. in 1987 from complications of diabetes.

It wasn’t until after his passing that he heard his great uncle’s story and wanted to learn more. Crane began researching Atwood and his involvement in the war.

“I didn’t even know he was still alive,” said Crane. “So, there’s always this sort of mystery of uncle Vincent and what had happened to him. As I got older I got interested in finding out what happened to this guy in France.”

“I get a little choked up when I talk about it,” said Crane. “I just think what kind of hell he went through. I get mad because I wish I had known he was still alive. I wish I knew [about him] before he died because I would have liked to have met him and just asked him anything.”