By Gerald Isaac and August Pelliccio, SCSU Journalism Students.

Gerald Isaac and August Pelliccio, journalism students at Southern Connecticut State University, reported this story in 2018 as part of Journalism Capstone coursework on World War I.

The Mark VIII tank was an important innovation for America’s effort in World War I, and Col. James Dudley Skinner played a role as an engineer designing the first prototype in Bridgeport.

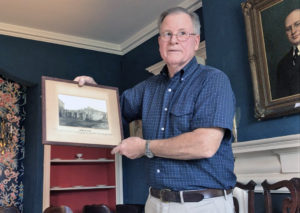

“They got the prototype built by the fall of 1918,” said David Sturges, Skinner’s grandson, “and they turned it over to the secretary of war.”

Sturges, 77, of Southport, said after the Battle of Somme, the British Army had demand for an improved tank. Skinner’s team in Bridgeport worked with the British military to engineer, build and test the Anglo-American Mark VIII tank.

Skinner was tapped for the job because of his credentials as an engineer. He received his bachelor’s degree from Yale in 1895, and completed a Master of Engineering degree at the University of Colorado in 1915, according to a 1959 Bridgeport Post article.

When the United States officially entered the war in 1917, Sturges said the Army was short of professionals to staff its Officers Reserve Corps, and Skinner was sent to Bridgeport.

Sturges said the city was a “war supply center,” and Skinner was put in charge of its armament and fuel industry, “overseeing the things they needed abroad were produced at a certain rate and sent overseas.”

Within one year, Skinner was appointed captain of the corps, and positioned as Bridgeport’s fuel administrator, according to the Bridgeport Post article.

“They ended up assigning him as the war department’s war board representative,” Sturges said.

The first official test of the Mark VIII was Oct. 31, 1918, in Bridgeport, according to the Quicksand Foundation, an online war-focused archive. The prototype was 35 feet long, and weighed over 40 tons.

Testing proved the tank’s ability to cross obstruction trenches 14 feet wide without the need for a bridge, and destroying trees with 2-foot diameter trunks, according to the Quicksand Foundation.

During World War I, Bridgeport was home to Remington’s 1.5 million-square-foot manufacturing facility. According to historian Carolyn Ivanoff’s lecture series, “The Great War and the Striking Summer of 1915,” the facility was the world’s largest building at the time of construction.

Skinner also supervised output of the Bridgeport Brass Co., Sturges said, when it was manufacturing engine parts for Navy Destroyers.

“A lot of engine parts were made of brass,” said Sturges, holding an authentic bearing cuff designed by Bridgeport Brass which he described as being “quite heavy.”

Sturges said in terms of engineering, ammunition was his grandfather’s specialty. Skinner was head of a team putting together essential weapons and vehicles that would be used to aid victory in World War I.

After the success of the Mark VIII prototype, Skinner resumed his service overseeing the production of artillery, maintaining an up-to-date knowledge of where guns were going.

“It was the era of the all-gun and big-gun Army,” said Sturges.

After the war’s close, Skinner continued working toward furthering innovation of military arms, said Sturges.

“He was a part of the effort to [mobilize] field guns for army artillery,” he said. “One of the things they did was take naval guns, 12-inch up to 15, and mount them on railroad cars and tow them around from place to place on a hypothetical ‘front.’”

Skinner was promoted to major in the Ordinance Department of his corps in March 1919, and to lieutenant colonel in 1924, according to the Bridgeport Post article.

In his time, he also oversaw the production of Springfield Rifle models being manufactured in Connecticut on contract. According to Sturges, the focus on the East Coast was to create a “big gun” artillery.

“When you hear the term ‘big-gun Army,’” said Sturges, “that was the effort, and he was very much part of that.”

Bridgeport had been a city that contributed important innovation to World War I, Sturges said, and his grandfather had a vital role.

“It was a war-defense city” said Sturges, “from start to finish.”

Skinner remained in inactive reserve until the war board commission’s expiration in 1941, according to the Bridgeport Post article, ending his military career as a colonel, at the age of 69.

“Believe it or not, he wanted to go into World War II,” Sturges said. But at that point, it was time to retire.