All we could do is watch the bodies float past’

by Kathryn Burton

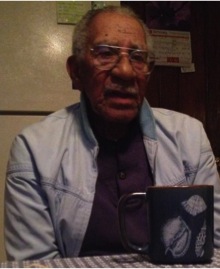

ANSONIA, Conn. — The room automatically felt lighter when Alfonzo Smith walked in and sat down. There is something about the way this world has changed that amazed him. “Smitty,” as he is known by his friends and family, has had quite a life. The people of this generation may be the biggest change he has witnessed.

Kids may not get to experience being drafted. However, there is so much war and destruction going on all around us these days that it is hard not to feel some animosity during everyday life. He believes that all people hear these days on the news is negative issues that are happening and they seem to not be getting any better.

“I feel bad for your generation and the generations to come,” said Smith. “Not only because of the endless war, but the respect for others around you just isn’t the same as it was back in my day.”

If a child ever talked back to a parent when Smith was growing up parents would have whipped the kid with a switch.

“We would have gotten beaten for talking back to an adult, not only that, when we got home and our parents found out when we did, they would make us go get a switch from a tree to beat us with again, and I grew up just fine,” Smith said.

Kids these days don’t get disciplined like they used to. They get away with a lot more because now it is not right to hit children, but Smith believes that a little slap to put a kid back in line never hurt anybody.

He described how kids just don’t show the same respect, to not only their families, but to strangers as well.

“Respect has changed a lot today from back in the day,” he said. “I am not sure where it went, but most kids sure don’t have it.”

Being 91, Smith grew up during the Great Depression.

“I lived a pretty normal life considering the downfall in the economy,” Smith said.

Smith lived a decent childhood in Ansonia. He got up in the morning and went to school like other children his age. Back then he walked back and forth to school. There was no other transportation. They got up, dressed for the weather and started their walk.

“After school me and a bunch of neighborhood kids would change into our play clothes and go find a field. Once we found an empty field we would always play some sort of sport,” he said. “Some days we would play football, other days it would be baseball.”

Food was rationed. Parents would go downtown to City Hall where there would be a wagon full of food, mostly non-perishable food items, like beans. This food was for the people who couldn’t afford anything during the time of the depression.

“What mama made for food is what you were gonna get,” said Smith. “There was no ‘I don’t like this or I don’t like that.’ You didn’t like it, you didn’t eat.”

He talked about there not being enough food for them to be too picky with. What people had was what they used with caution. Women cooked a lot of the times for their family and others.

During this time everybody helped one another out. Every mother mothered the neighborhood kids. There was nothing kids could get away with growing up in the 1920’s.

“If you got out of line your friend’s mother would beat you. Then you would get a beating from your parents when you got home for misbehaving in the presence of other people,” he said.

For the most part Smith described growing up like any normal child. Every Sunday families would get dressed up in their Sunday best and attend church. No matter how bad the economy was and the struggle for basic survival, there was always time for church.

“That is what amazes me with the difference between people now and people when I was growing up,” Smith said. “Young people don’t know how good you have it, but on the other side of things, all you see is war and destruction.”

Throughout his schooling he had little odd jobs around town to help his parents put food on the table. He would work a small paper route, and maybe even some hours at a little corner store—nothing much, but it was something.

He was drafted into World War II just after graduating from a technical college. He and a bunch of his friends he went to college with got their draft letters all at the same time.

“We were told at one point that if we went to technical college we would have less of a chance getting drafted, but we all ended up getting our letters,” said Smith.

He speaks about his time during the war. His job was to supply the troops with working guns and other artillery. He was first stationed in Aberdeen, Md., where he was put into small-armed weapons, which was maintaining and repairing different types of guns and weapons. He repaired anything from rifles to automatic machine guns.

There was one point during the war where air raids flew over him and his troop. Everybody scattered to hide so they didn’t get hit.

“I remember them telling us, ‘Don’t hide in the hedge rows.’ So I hid underneath one of the trucks to get away from the raids,” he said. “We lost 59 men that night.”

He was there on D-Day when the troops stormed the Beach of Normandy. His platoon was not allowed on shore. He didn’t know why at the time, but he figured it had something to do with their being black. His general, George C. Patton, got angry. Smith remembers what Patton said to his troop before storming his way through the beach:

“Patton told us, ‘If you see me, I don’t know you and you don’t know me’,” He said.

He wanted to make sure his troop stayed safe even though he was going to storm into to Germany and onto the Beach of Normandy Beach of Normandy without them. That was for the troop’s safety and Patton’s. It was safer to “not” know each other.

Twelve days passed and they were stuck in the canal. After those twelve days passed they were finally able to get onto the beach.

“All we could do is watch the bodies float past us and count them as the days slowly passed,” Smith said with sorrow. “The smell was horrific and the sights were unimaginable. Seeing the men of other platoons fall and there was nothing we could do about it. It was heartbreaking, very heartbreaking. When we finally did get onto the beach, I just remember seeing all these bodies just lying there.”

Smith spent three years serving the country, and afterward saw so many life changing events happen in his life, from The Great Depression, World war II, the Holocaust, the Flood of ‘55 in the lower Connecticut Valley: Ansonia, Seymour, Derby, and Shelton.

After Smith got back from the service he started to settle down into a life. He got married and had four children—two boys and two girls. After he had kids he worked as a finisher for the longest time. After that job he worked for the postal service for just over 20 years .He got very involved with his community. His son, Ronald, volunteered him to couch baseball since he himself was in a semi-pro league for a while in his younger years. He has been on the Recreation Committee since his children were little helping with sports decisions in the town of Ansonia, and he is still on that committee.

Smith has always been an active part of Ansonia for most of his life. He is always willing to lend a helping hand in his community.

“I have no regrets, on the other hand I have a lot of regrets, but at the end of the day, I am happy with my life,” he said.